Akka anti-patterns: too many actor systems

Contents

Admittedly I’ve seen this one in use only one time, but it was one time too many. For some reason I keep seeing clients come up with this during design discussions and reviews though, therefore it makes it into the list of Akka anti-patterns.

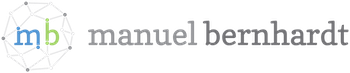

What I am talking about is this:

Reasons I hear for this design:

- isolation of concerns: each ActorSystem is separated, hence failure of one system does not affect the other

- custom classloading in the ActorSystem, dynamically loading libraries and isolating them between systems

- using multiple Akka versions without having to restart

And I am not talking about designs where there are 2 or 3 ActorSystems on the same JVM here, but possible hundreds if not thousands. Now, Akka itself does not share any global state so you can theoretically pull this off. But should you?

To me, this type of design is the result of an incomplete understanding of Akka, or a lack of trust in its abilities. Even though the Akka documentation tells you to relax and take it easy, you may have concerns as to things not working out the way they should. Let me be clear at this point: you can (and should) trust Akka when it comes to fault tolerance and recovery. That’s what it is good at. Seriously. I’ve seen the thing juggle millions of messages without breaking a sweat, maxing out network I/O and crashing remote systems it was calling into. It’s battle-proven technology.

There’s just a few things you need to know about to use it correctly, which we’re going to cover now.

Dispatchers are your friends

Each Actor has a dispatcher provided by the ActorSystem. Dispatchers are what makes Akka actors tick. They are backed by a thread pool and decide how exactly messages are being processed by actors.

Hence if you’re afraid of one actor or set of actors hogging all of your systems' precious threads, use dispatchers. You can define custom dispatchers programmatically or via configuration, making sure that potentially dangerous actors are being run by a dispatcher that has only a fixed amount of threads at its disposal. No more nightmares about one part of your actor hierarchy blocking everyone else.

Supervision FTW

When it comes to handling failure, there really is nothing like supervision. I have discussed supervision and actor hierarchies at length previously so I won’t repeat myself here. I’ll just point out one thing: if you are afraid that your entire ActorSystem is going to crash because of one or more actors, simply define a supervising actor for them that has the appropriate supervisor strategy. Essentially, do not let failures escalate too high in the hierarchy and apply whatever recovery mechanism is appropriate (if you have to wait for a system to become available again, you may consider using the BackoffSupervisor pattern.

Remember: everything that leads the root guardian to restart too many times will eventually lead to your system being shut down. So do not create flat hierachies.

Clustering and replication

Do not rely to your one machine (or worse, virtual machine) to always be there. And if you are concerned with service continuity during upgrades of the software, replicate your application using clustering which lets you take down and upgrade nodes individually. There is just a few things you’ll want to make sure of:

- protocol compatibility: use protobuf (or equivalent) for message serialization and allow for an upgrade path so that old and new nodes can co-exist

- make sure that there is no single point of entry to your cluster communicating with the outside world since that would essentially defeat its replication capability

Why running 1000+ actor systems on one JVM is a bad idea

If you are still not convinced, let me give a few reasons as to why running many ActorSystems on the same JVM is not a good choice.

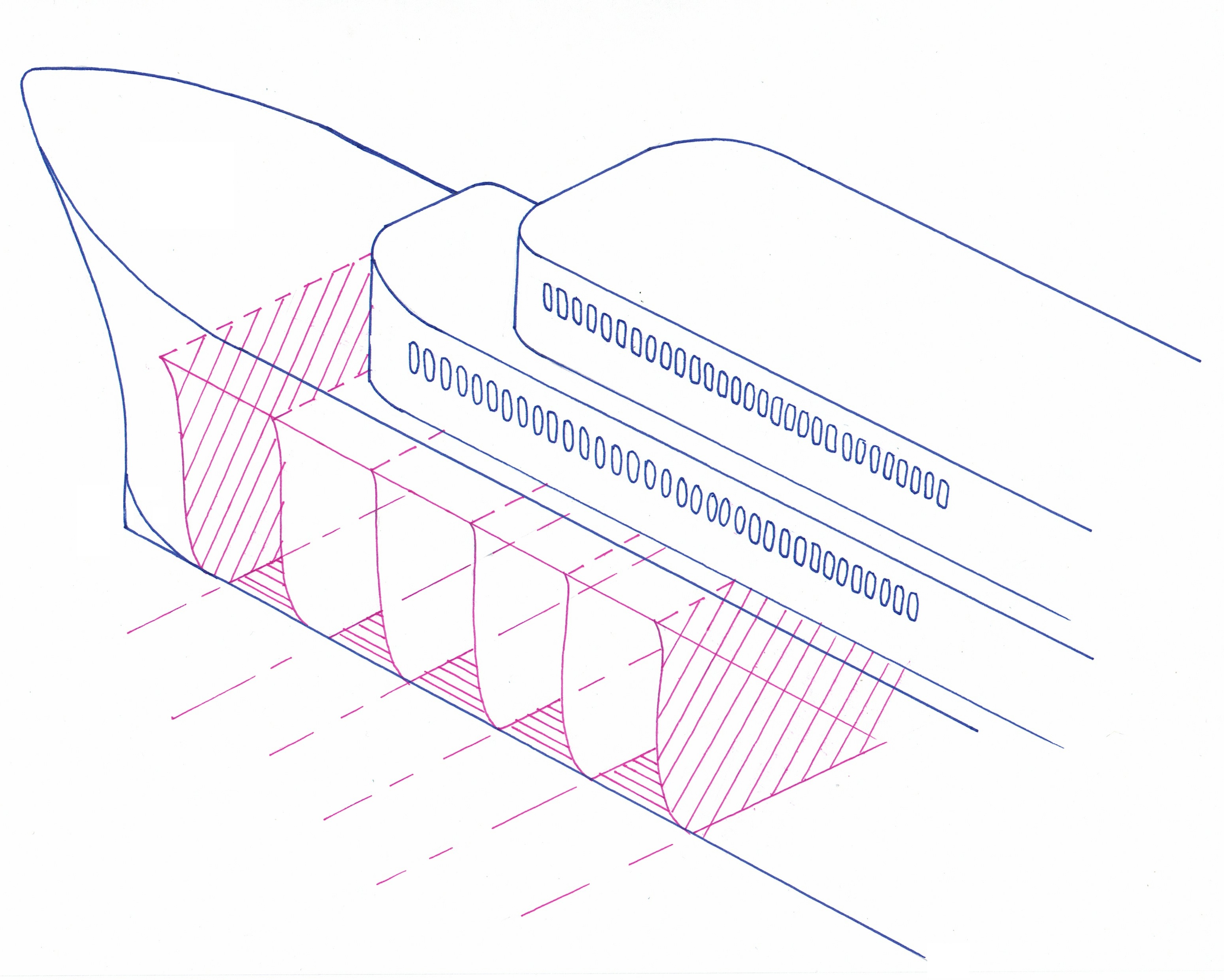

First of all, if your systems are part of a cluster (they should be, this is where all the fun stuff is happening) then there will be a lot of useless I/O overhead. Each system, which is to say each cluster node will gossip with other possibly remote nodes about the state of the cluster using the same wire. And the systems will likely talk to each other, since this is what actors usually do. As awesome as Akka’s failure detector is, this may result in nodes becoming flaky, especially when the network I/O load is maxed out.

Next, each ActorSystem comes with a default dispatcher which is backed by a fork-join pool. This pool does a really great job at balancing work and available threads. That is, if you run 1000 of those puppies on the same JVM, this will end up creating way too many (virtual) threads, killing the performance in the process. Ideally you want as many threads as you have CPU cores with optimal utilization.

And last but not least, you loose all the benefits and opportunities of supervision.

That’s it. I hope I managed to convince you that this design is not a good idea. Lay back, and let Akka do the heavy lifting!