Tour of Akka Typed: Cluster Sharding

Contents

Update 21/11/2019: Fixed comment about shardId extraction in relation to ShardingEnvelope

Welcome to the fifth part of the Akka Typed series! In this part, we’ll leave the safe harbor of a single JVM and sail into the seas of distributed systems by exploring a key features of Akka Cluster with the typed API: Cluster Sharding. If you want to get a more in-depth introduction to Akka Cluster, I invite you to check out the article series on this topic.

Before we get started, here’s a quick reminder of what we’ve seen so far: in the first part we had a look at the the raison d’être of Akka Typed and what advantages it has over the classic, untyped API. In the second part we introduced the concepts of message adapters, the ask pattern and actor discovery. In the third part, we covered one of the core concepts of Actor systems: supervision and failure recovery. Finally, in the fourth part, we covered one of the most popular use-cases for Akka: event sourcing.

Redesigning the system for scale and resiliency

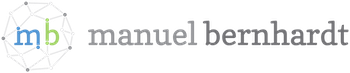

Up until now, our payment handling system is quite linear in the way it works and not (yet) fit for a higher throughput of requests. When having a critical look at the initial design this becomes quite visible:

Indeed, the request handling is completely sequential: in order to be processed, the request (or its derivates) must flow through the PaymentHandler, then the Configuration, then the CreditCardPaymentProcessor and then back.

Actors handle one message at the time. Our PaymentHandling and CreditCardProcessor actors will deal with one message after the other and use (at most) one CPU core for this purpose each. The same holds true for Configuration, but since this actor should in fact be a persistent actor (it is possible to modify the configuration), there can only be one of its kind. But scaling out isn’t the only issue we need to address in order to build a truly reactive payment system.

Right now, if our PaymentHandling actor crashes while a request is being processed, there’s no mechanism to ensure that it will be started again. In fact, the system won’t even remember that there was a request to handle in the first place. We could of course turn PaymentHandling into a persistent actor, remembering all the in-flight requests - but this would quickly turn into a bottleneck for the entire system.

Instead, let’s explore a slightly different approach for which we’ll need to refactor our current PaymentHandling actor (which won’t hurt anyway, since it has become rather large already). We’ll be making use of a variation of the per-session child actor pattern: for each incoming request, we’ll delegate the request handling to a dedicated actor that itself will be persistent.

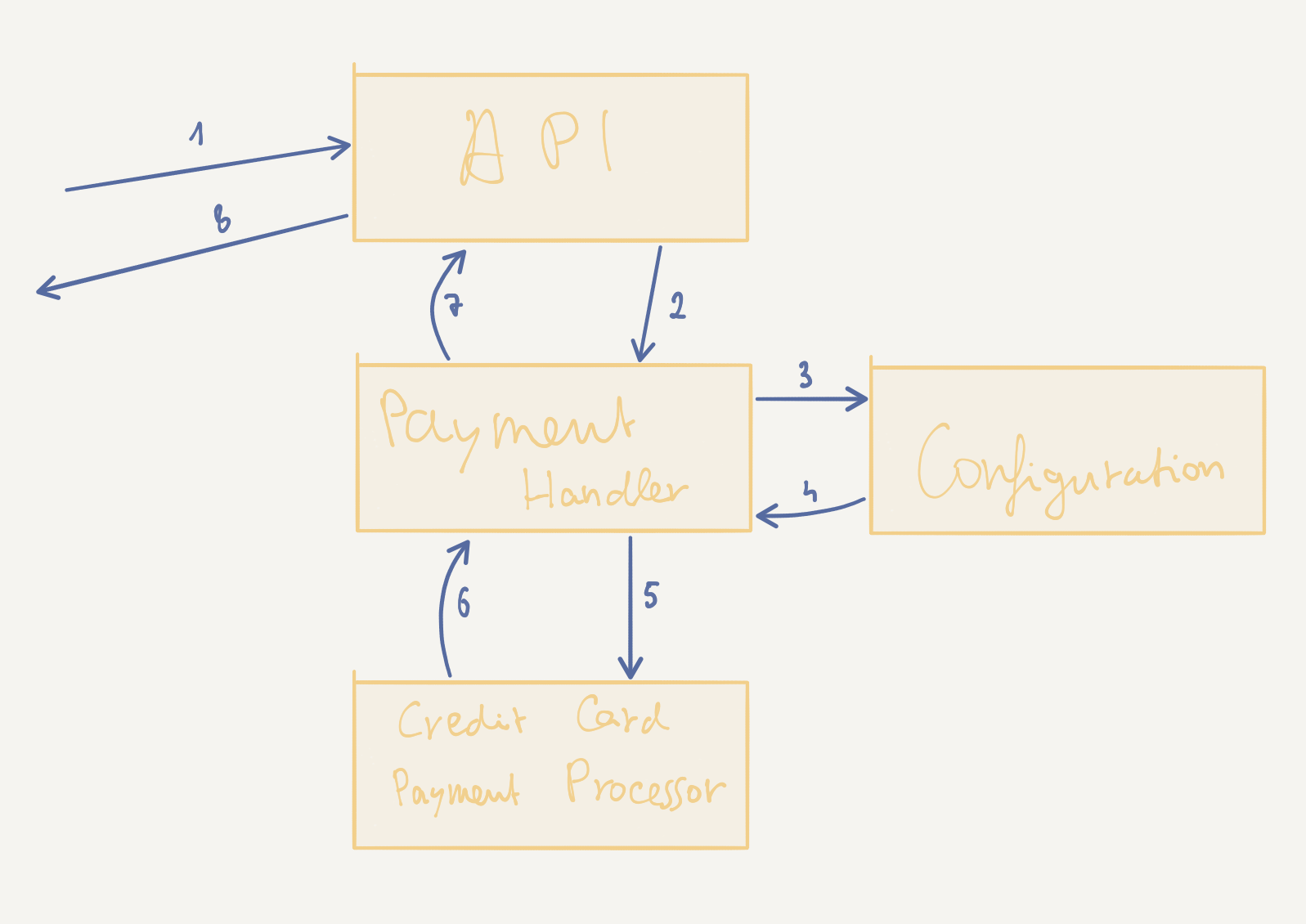

From a logical perspective, this is what our system will now look like:

In order to scale out on as many machines as we require, we will be making use of three Akka Cluster features that we will be exploring in more detail later (in the rest of the article, and in the next one):

PaymentRequestHandleractors will be deployed using Cluster Sharding (in green on the figure above)CreditCardProcessoractors will be scaled out and deployed via Routers (in violet in the picture above)- The

Configurationactor will be deployed as a Cluster Singleton (in blue next tonode 1on the figure above)

Scaling out request handling with Cluster Sharding

Our existing PaymentHandling actor is taking care of a few things:

- it tracks the deployment of payment processors (thanks to the receptionist we explored in part 2 of this series)

- it receives incoming payment requests

- it queries the

Configurationactor - it forwards requests to the appropriate

Processor

We will now proceed to splitting this actor into two pieces:

- the

PaymentHandlingactor which tracks deployed payment processors, sets up cluster sharding and delegates the request to a newPaymentRequestHandlerentity - the

PaymentRequestHandlerthat handles a request by queryingConfigurationand then the appropriateProcessor

Step 1: splitting PaymentHandling in two

Let’s start by simplifying our protocol. We’ll now be able to deal with two types of messages: the incoming payment requests and the updates to receptionist listings (which are not part of the public protocol). Our protocol will therefore be:

| |

Now, let’s simplify the actor to a minimum so it can listen to changes in available processors and create dedicated actors per request. We will start without sharding by simply creating new child actors for the moment:

| |

That’s for the easy part. Let’s now look into the PaymentRequestHandler. It has to take care of 3 things:

- accepting payment requests and retrieving the configuration

- handling the configuration response and calling the processor

- handling the processor response and relaying the response to the original client

This brings us to the following protocol (public and internal):

| |

Note that as per the style guide, we have made internal messages private.

When it comes to implementing the actor itself, we will use 3 behaviors to reflect the 3 states the actor can be in (waiting for a request, waiting for the configuration, waiting for a processing reply):

| |

The full implementation can be found in the source code for this article series.

Step 2: making the PaymentRequestHandler persistent

In order to be able to remember that we received a payment request in the face of crashes we need to make the PaymentRequestHandler persistent. We’ll do so by persisting events:

| |

(note: we’re persisting an ActorRef[Payment]in this example and are exposed to the risk of this reference not being available anymore after de-hydration. For the purpose of this example, we’ll assume that the actor reference of the client is stable and always available to recovered actors - but be aware that this may not always be the case, such as for example when catering to clients backed by an Akka HTTP endpoint)

Just as we have seen in the previous article on event sourcing with Akka Typed, we also need to define the State for this actor. Conceptually, it functions as a finite state machine capable of handling different types of commands in different states (just as the ones we modeled using different Behavior-s previously):

- when nothing has happened yet (initial, blank state)

- when having accepted a request to handle

- when receiving the processing result

Note that we don’t model an explicit state for waiting for the configuration - we will just fetch it anew should we need to do so. This leads us to the following state definition:

| |

Note that technically, in the current implementation, we will be stopping the actor once the payment has been processed. That is, it could be that the client sends us the same request twice - and in this case, we need to remember that we are done in order to provide an idempotent reply, which is why we explicitly model the PaymentProcessed state.

Our actor now gets the following structure:

| |

The full implementation of the persistent actor can be found in the sources of this article. Note that the sources are not written in the “handler as part of the state” pattern - this is left as an exercise to the reader.

Step 3: setting up sharding

Let’s now get to the interesting part: turning the request handler into a sharded entity.

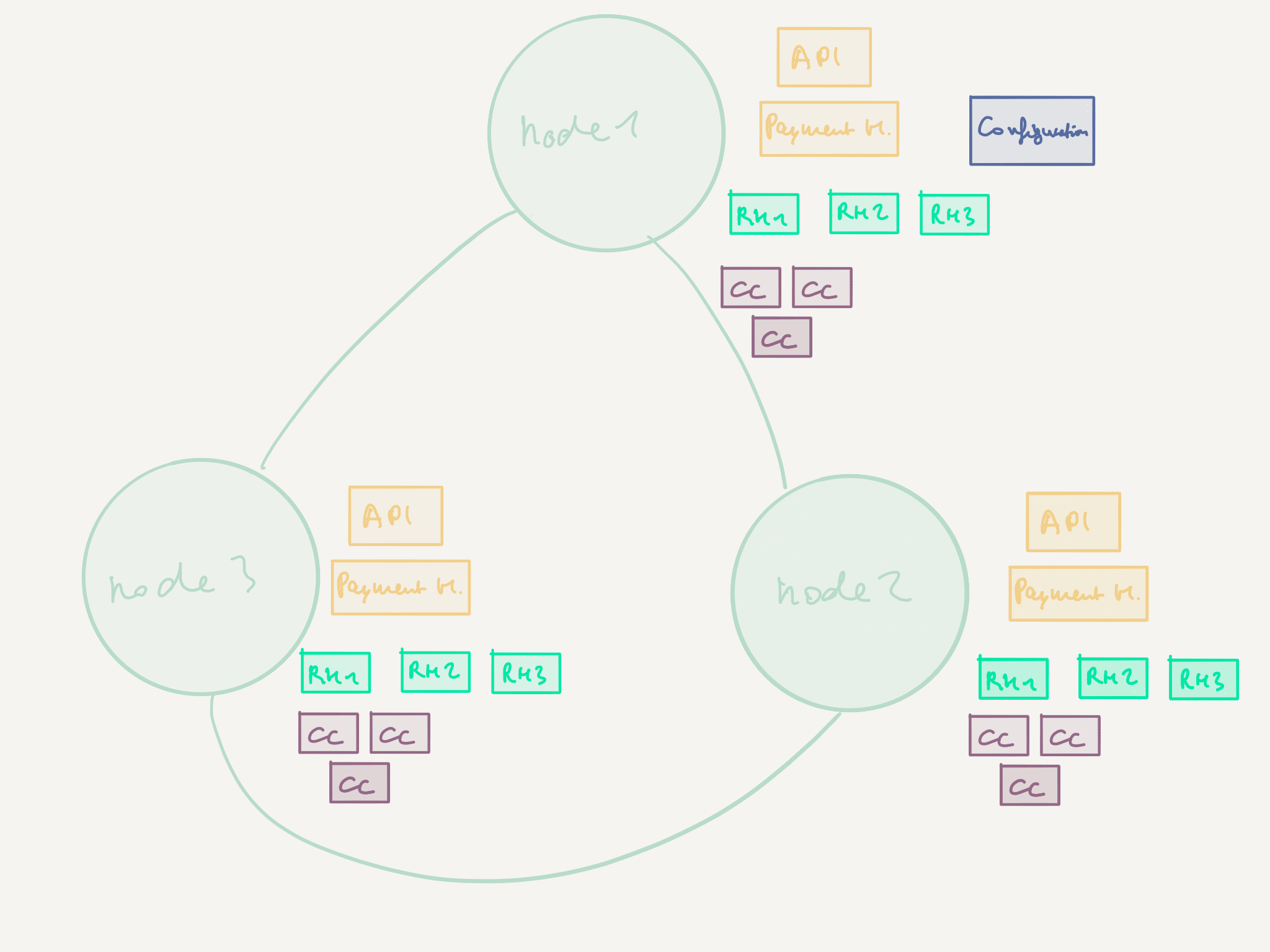

In Akka Cluster Sharding, the actors to be sharded are referred to as sharded entities. They each have an identifier that is globally unique across the entire cluster. Those sharded entities are themselves part of so-called shards, which you can think of as containers for holding a number of sharded entities. The reason for this design is to cut down on communication and coordination overhead when a node is shut down and its shards need to be re-created someplace else, or when the distribution of entities in the cluster becomes unequal and a shards must be re-balanced. Within a cluster node, the shards are managed by a shard region.

In order to take advantage of Cluster Sharding, we will hand over the creation of the PaymentRequestHandler actors - as well as the decision of where they are deployed (i.e. which node in the cluster) and for how long they stay around in memory - to Akka. We won’t have to worry about operational details such as failover or load balancing (where actors are deployed) ourselves - as the Cluster Sharding extension will take care of it for us.

That doesn’t mean we don’t have anything to do. When setting up sharding there is a key decision to be taken (and it should not be taken lightly): how to distribute shards on nodes.

The distribution of shards on nodes is important because it directly influences the performance of the overall system:

- if there are too few shards in relation to nodes, then the load distribution will be uneven as the shards will get “too big”, i.e. they will contain too many entities all the whilst some nodes will not be hosting any shards.

- if there are too many shards in relation to nodes, the shards will be “too small”, each only containing a few entities. Moving individual shards will be fast, but as there are many, there will be quite some communication overhead caused by having to frequently re-balance shards in order to keep the load distribution equal in the cluster (i.e. there will be a lot of re-balancing, which in turns also impact latency).

The decision of how many shards to allocate is taken by defining a sharding algorithm based on the entity identifiers - basically, it should be possible to infer from the entity id which shard the message should be routed to. This algorithm can’t, of course, be changed while the cluster is running (i.e. you cannot do a rolling deployment that introduces a new sharding algorithm), therefore it should be chosen carefully.

Let’s now have a look at how to set up sharding in the PaymentHandling actor, which used to spawn the PaymentRequestHandler children directly.

First, we need to add a new dependency to our project:

| |

Next, we retrieve the sharding extension:

| |

So far, so good. Let us now initialize sharding for our entities. For this, we need mainly 4 things:

- an

EntityTypeKey[MessageProtocol]used to describe which entity is being sharded - including, as its signature suggest, its message protocol - a

MessageExtractorthat knows how to extract theentityIdof a message as well as how to turn anentityIdinto ashardId - a factory method for building the behavior of the sharded entities from an

EntityContext[MessageProtocol]

a stop message sent to the sharded entity before being shut down (before rebalance, passivation, shutdown, etc.). This is particularly important for persistent actors, as the default is to use aPoisonPillwhich immediately stops the actor, regardless of whether everything has been written to the journal

With that in mind, let’s get started. The entity type key is rather straighforward:

| |

For the message extractor, we will use the provided HashCodeNoEnvelopeMessageExtractor[MessageProtocol] which allows to specify how to extract the entity id from a message, and then takes care of deriving a shard identifier based on the hashcode of the entity id:

| |

Note that we have made orderId a field of the PaymentRequestHandler.Command protocol in order to use this approach.

An alternative to using a property of the message (in most cases, a unique identifier - in our case we use orderId) in order to derive the entityId and shardId “outside” of the messages is to capture these properties as part of the messages, with the caveat that the entity needs to be aware of this sharding-specific protocol.

Finally, let’s assemble everything and start the shard region. We will use a new custom stop message added to the protocol of the PaymentRequestHandler:

| |

The behavior factory takes an EntityContext[MessageProtocol] that provides useful context, such as the entityId. As you may have noticed, we’ve had to adjust the behavior factory of the PaymentRequestHandler to allow creating entities: we’re now providing it with:

- the

orderIdof the order at hand - a

PersistenceIduseful for our persistent entity - a reference to the configuration actor

The PersistenceIdis constructed on the basis of the TypeKey and the entityId, which allows entities of different types to have the same identifier (in sharding, the entity identifiers must be globally unique accross the cluster).

The rest of the payment request information is provided to the entity as part of the HandlePaymentRequest message.

In order to send messages to the entity, we use the shardRegion obtained previously:

| |

A sharded entity is be created by its shard when a first message is sent to it. If it is idle (i.e. if it receives no messages) for 120 seconds (by default) then it will be passivated, i.e. it will receive the stop message from its parent shard.

Step 4: resuming processing in case of crash

There is one more thing we need to take care of. If the node which handles the request crashes, or if the entity is passivated while processing the request (for example, while waiting for a reply of the configuration), we need a way to bring it back up to life and to resume processing.

We will be using a feature of Akka Cluster Sharding adequately called remember entities: when the shard that holds the entities is re-allocated (after re-balancing or after a crash), all the entities it holds will be started again automatically. This feature needs to be explicitly enabled in the configuration:

akka.cluster.sharding.remember-entities = on

(note: as you can imagine, there’s a cost associated with using this feature - it should not be used for systems that holds a large number of entities per shard, as it slows down the rebalancing of shards)

What’s now left to do is to figure out where we left of and resume processing. For this, we’ll handle the RecoveryCompletedsignal and take appropriate action:

| |

This is it for this article! In the next one, we’ll continue looking into the Akka Typed Cluster extensions with routers and Cluster Singleton.

Concept comparison table

As usually in this series, here’s an attempt at comparing concepts in Akka Classic and Akka Typed (see also the official learning guide):

| Akka Classic | Akka Typed |

|---|---|

typeName String | TypeKey |

ClusterSharding(system).start(...) | ClusterSharding(system).init(...) |